In Iran, the qahveh-khaneh (coffeehouse) has traditionally been far more than just a place to drink tea or coffee; it is a deep-rooted social institution with centuries of history, reflecting the cultural, social, and even political transformations of Iranian society. These popular establishments provided a vital space for gatherings, lively discussions, information sharing, entertainment, and at times, even the shaping of significant societal and political decisions.

From the Safavid era, when the first coffeehouses emerged in major Iranian cities like Isfahan and Qazvin, to the present day, where some continue to thrive despite the rise of modern cafés and contemporary spaces, these venues hold countless untold stories and have witnessed the full spectrum of the nation’s history. Coffeehouse culture, with all its unique characteristics, remains an inseparable part of Iranian identity and collective memory.

In this article from Foodex Magazine, we aim to explore this rich and vibrant culture – from examining the historical roots and diverse functions of coffeehouses in bygone eras to reviewing their challenges, transformations, and place in Iran’s dynamic contemporary society, including a brief look at similar traditions in neighboring countries. Our goal is to present a comprehensive and precise picture of this cultural and social phenomenon.

If you are interested in gaining a deeper understanding of food and beverage cultures in Iran and around the world, we recommend exploring other specialized content in our Food & Drink Tourism section on the Foodex blog. Join us now as we embark on a journey into the fascinating world of Iranian coffeehouses.

Historical Roots: From Sherbet Houses to the Rise of the Coffeehouse

Before tea and coffee became widespread daily beverages among Iranians, it was various herbal and fruit sherbets (sharbat) that held a special place in the culture of hospitality and for quenching thirst. Establishments known as ‘sherbet-khanehs’ (sherbet houses) operated in different Iranian cities, serving as centers for preparing and offering these delightful traditional drinks, and sometimes also functioning as venues for brief social gatherings and conversations.

The earliest indications of coffee’s arrival in Iran date back to the prosperous Safavid era. It appears that coffee, more prevalent at the time in the vast Ottoman Empire and Arab lands, initially garnered attention for its medicinal properties and as a stimulant and energizing substance. This novel beverage then gradually found its place as a pleasurable drink among some courtiers and the upper echelons of society, subsequently making its way to other social strata.

Almost concurrently with coffee, or perhaps shortly thereafter, tea also made its way to Iran via eastern trade routes, particularly from China and India. Although coffee initially managed to secure a special status among enthusiasts, factors such as the greater ease of cultivating and processing tea in regions geographically closer to Iran, the development of its trade, and its greater compatibility with the general palate, gradually led to the ever-increasing consumption of tea among the populace. Eventually, tea was established as the primary and indispensable daily beverage for Iranians.

With the growing interest in and consumption of these two new beverages, especially coffee during its initial surge in popularity, ‘sherbet-khanehs’ gradually witnessed a transformation in their function. Many of these traditional establishments adapted their spaces to offer coffee, and later tea, thus laying the foundations for the first ‘qahveh-khanehs’ (coffeehouses) in Iran. This evolution marked a turning point in the formation of the coffeehouse as a distinct social institution. Of course, the acceptance of coffee as a public beverage was not always without challenges; for instance, during certain periods and in some regions, such as the reign of Sultan Murad IV in the Ottoman Empire, restrictions and even prohibitions were imposed on its consumption and on coffeehouse activities. However, in Safavid Iran, coffeehouses seem to have met with greater societal and even some governmental approval, leading to their rapid expansion.

The Golden Age of Iranian Coffeehouses: The Safavid Era

The Safavid era, particularly from the reign of Shah Tahmasp I onwards, can be considered the starting point for the flourishing and expansion of coffeehouses in Iran. With the growing popularity of coffee consumption, the first coffeehouses began to take shape, initially in the then-capital, Qazvin, and subsequently in other large and prosperous cities like Isfahan. These nascent establishments quickly transformed into gathering places for hosting dignitaries, statesmen, scholars, artists, and various other social classes, acquiring a role far beyond that of a mere resting place.

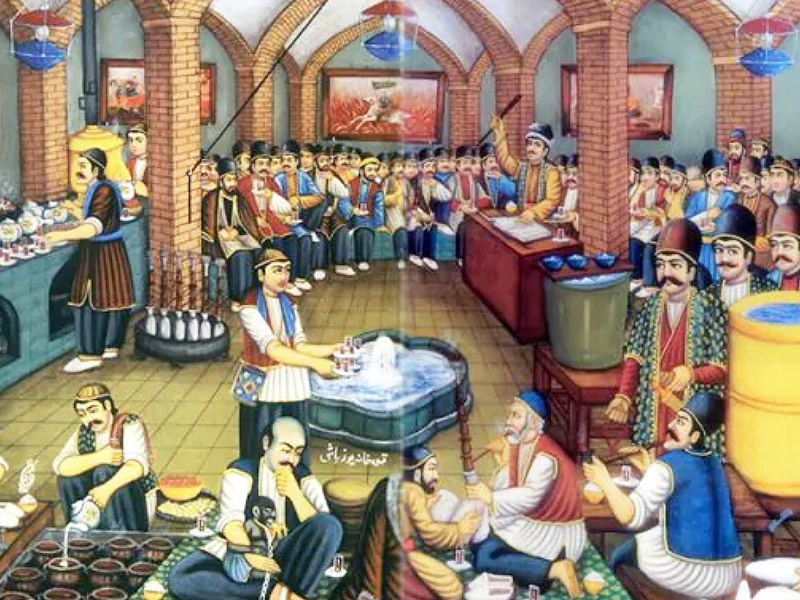

The early architecture of Iranian coffeehouses during this period typically featured a spacious, unified area, often without numerous view-obstructing pillars or curtains. Since the majority of patrons at that time were men, there was no perceived need in the initial designs for separate sections like an andaruni (the traditional private inner quarters of a house, typically for women and implying seclusion) or dedicated side rooms (otāq-e gushvāreh). For greater guest comfort and in line with the culture of Naqqāli (storytelling) and poetry reading (which we will discuss in more detail later), small verandas or arched alcoves (tāq-nemāhā) were often built around the main space. Additionally, a more prominent, decorated, and carpeted area known as the ‘shāh-neshin’ (literally ‘king’s seat’, designating a VIP or honored section) was designated for high-ranking individuals, special guests, and dignitaries. Each person would sit in a specific area based on their social status, wealth, and prestige, occupying themselves with the qalyan (water pipe), tea, or coffee, while observing the ongoing cultural performances. Important political, social, or guild meetings were also sometimes held in these shāh-neshins, away from the general public, potentially influencing significant affairs of state or community.

The zenith of the flourishing, importance, and influence of coffeehouses in Iran should be sought during the long and fruitful reign of Shah Abbas I Safavi (Shah Abbas the Great), a period often referred to as the Golden Age of Safavid history. In his magnificent capital, Isfahan, especially surrounding the grand Naqsh-e Jahan Square and near royal palaces like Ālī Qāpū, numerous large and splendid coffeehouses were established. Many of these establishments even hosted the Shah himself, his companions, and courtiers. It is reported that Shah Abbas had a particular fondness for these spaces and sometimes met with official guests and foreign ambassadors not only in palaces like Chehel Sotoun but also within these bustling public coffeehouses, perhaps for variety or for closer interaction with certain segments of society.

Shah Abbas’s presence and patronage also had a significant and profound impact on the cultural function of coffeehouses. Poets, scholars, and orators gathered in these venues to praise the Shah, present their new works, or participate in literary discussions. Consequently, in addition to the long-standing traditions of Shahnameh-recitation and epic Naqqāli, ‘poetry reading’ (sha’r-khāni) and literary circles also became primary and engaging programs in the coffeehouses of this era. Regarding the main beverage, coffee, it was typically prepared and served during this period in the same style prevalent in the Ottoman Empire and other parts of the Middle East: plain, bitter, without added milk, sugar, or other flavorings, presented in small, special cups – similar to what we recognize today as Turkish coffee.

The Beating Heart of Culture and Art: From Shahnameh Recitation to Coffeehouse Painting

In Iran, especially from the Safavid period onwards when they became primary public gathering centers, coffeehouses played a vital and unparalleled role in preserving, promoting, and even shaping popular oral traditions, performing arts, and visual arts. In a society where general literacy levels were relatively low until recent centuries, and where writing and reading were not widespread practices, these venues became the foremost hubs for transmitting stories, epic poems, moral teachings, and social news.

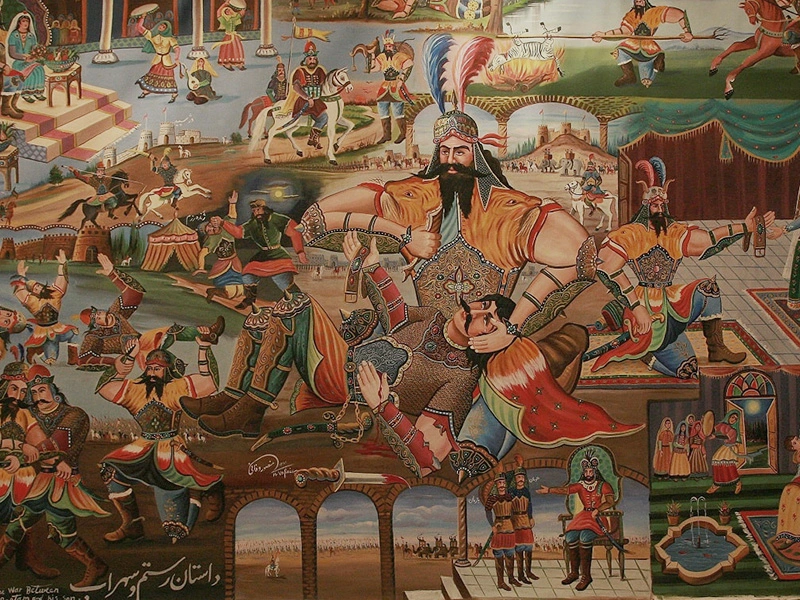

Shahnameh-recitation (Shāhnāmeh-khāni), the artful and passionate reading of the great epic poems of Hakim Abu’l-Qasem Ferdowsi with specific intonation, melody, and sometimes corresponding gestures, was one of the most popular and enduring cultural programs in coffeehouses. These performances not only kept the Persian language and Iran’s national stories alive but also reinforced concepts of heroism, chivalry (javānmardi), and patriotism among the audience. Alongside this, the art of Naqqāli, a form of dramatic solo storytelling using eloquent narration, body movements, and sometimes accompanied by illustrated scrolls (pardeh), was performed. Master naqqāls (storytellers) would skillfully bring to life stories from the Shahnameh, religious epics such as the tragedy of Karbala, and other heroic, historical, and romantic tales for hours to captivated audiences. Many folklorists and theater historians consider these coffeehouse performances to have served a function similar to modern theater for entertainment, education, and the transmission of cultural values in the society of that time.

In addition to ancient Iranian national and epic stories, following the officialization and growing importance of Shia Islam during the Safavid period and thereafter, the narration of the tribulations and virtues of the Shia Imams also formed an important and inseparable part of the content of Naqqāli and pardeh-khāni (scroll recitations). This rich oral and performing tradition gradually paved the way for the emergence and flourishing of another unique art form entirely associated with this space: coffeehouse painting (naqqāshi-ye qahveh-khāneh’i). To increase their impact on the audience, enhance the understanding of battle scenes or dramatic events, and also as memory aids, naqqāls would commission painters to depict key scenes from the narrated stories, be they epic or religious—on large canvases or directly onto the coffeehouse walls. These paintings, created in a distinctive folk style with vibrant colors and a direct, popular narrative approach, opened a new chapter in Iranian narrative and visual art, becoming one of the most prominent cultural symbols of Iranian coffeehouses.

Leisure, Smoking, and Other Pastimes

Coffeehouses in Iran were not solely venues for drinking tea and coffee or listening to storytelling and poetry; they gradually transformed into hubs for various forms of entertainment, leisure, and broader social interactions. Alongside the main cultural programs, games like backgammon (takhteh-nard) and chess (shatranj) gained considerable popularity among patrons, providing opportunities for friendly competition, displaying skill, and passing the time. This aspect further underscored the coffeehouse’s role as a multifunctional public space for relaxation and a break from daily work routines.

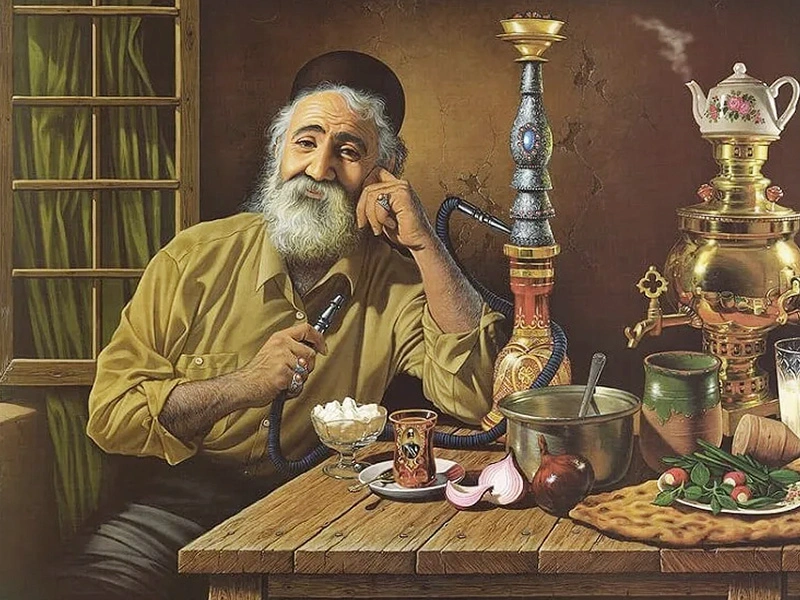

Another phenomenon that quickly became intertwined with coffeehouse culture in Iran, evolving into one of its inseparable symbols, was the practice of smoking. The Chopoq, a type of traditional long-stemmed pipe, appears to have become known in Iran from the early Safavid period. As some historical texts and reports from that era indicate, smoking the Chopoq was common even among courtiers and Shah Safi himself, with specific individuals responsible for preparing and ‘lighting’ (chāq kardan, literally ‘to make fat’ or ‘to fill’) the Chopoq for the Shah.

However, perhaps more significant, widespread, and culturally ingrained than the Chopoq was the use of the Qalyan, also known as a huqqah or water pipe, which rapidly spread throughout coffeehouses and subsequently into homes and private gatherings. Many historians and cultural researchers consider the Qalyan to be either an inherently Iranian invention or believe that its form and method of use were significantly developed and integrated into the culture within Iran, with some suggesting its origins might even predate the Chopoq. Numerous European travel writers who visited Iran during various periods of the Safavid and Qajar dynasties, including well-known figures like Jean Chardin and Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, extensively detailed in their precise observations the widespread practice of Qalyan smoking among Iranian men from different social classes, especially within the coffeehouse environment. During that era, the Qalyan was not just a pastime but had also become an integral part of hospitality rituals and social formalities.

Smoking the Qalyan and Chopoq in coffeehouses evolved into a social custom with its own unwritten rules and etiquette, forming an essential part of the experience of being in these establishments. This habit remained a significant part of daily life and primary leisure activities for many Iranian men until recent decades, even before the introduction and widespread adoption of cigarettes (which gradually became common in Iran about 80 to 90 years ago). Although the popularity of the Chopoq considerably declined with the rise of cigarettes, the Qalyan has managed to retain its place, particularly in traditional coffeehouses and certain social circles, to this day.

The Qahveh-chi (Coffeehouse Keeper) and the Social Structure of the Coffeehouse

Given the pivotal role of the coffeehouse as the main hub of neighborhood social life and a regular haunt for various segments of the populace, the Qahveh-chi, the owner and operator of the coffeehouse, also held a special status and considerable social prestige. He was not merely a tradesman or service provider but was often recognized as a trusted individual, well-informed about daily news and events, and sometimes even acted as a mediator in resolving local disputes or community problems. Some reports suggest that during certain periods, Qahveh-chis, due to their sphere of influence and extensive networks, were even noted or consulted by local or even governmental officials.

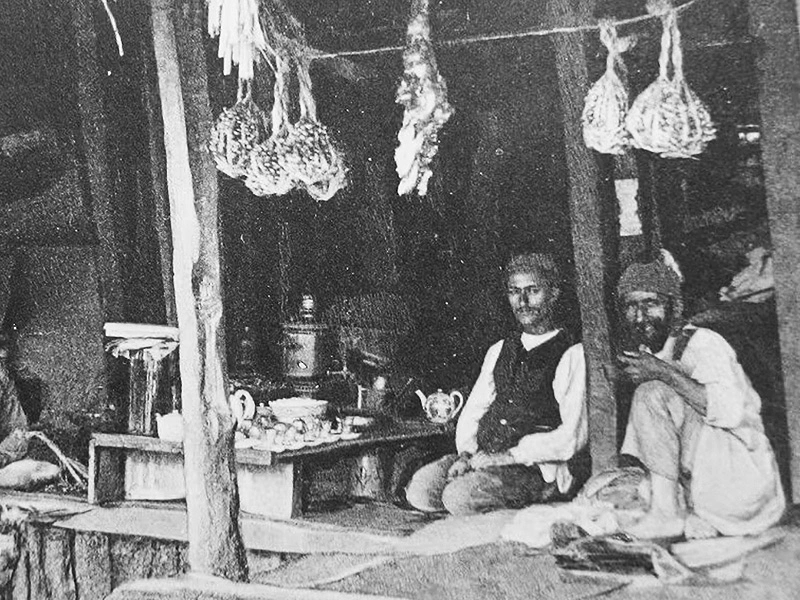

Running a thriving coffeehouse, especially during its peak periods of activity, required the collaboration of a team with specific and defined duties. An interesting structure and hierarchy existed among coffeehouse staff, indicating the relative complexity of this socio-economic unit. Based on some surviving descriptions and documents from those eras, this hierarchy could include individuals with titles and responsibilities such as: the Chāy-forush, or head tea man (often the most important person after the Qahveh-chi, overseeing tea preparation and service); the Pāy-e Samāvar, (assistant in charge of the samovar and keeping water boiling); the Vardast, (general helper performing various tasks); the Pādu, (errand boy for outside tasks like purchasing supplies); the Bāzār-row, (responsible for delivering tea or qalyan orders to shopkeepers and merchants in the bazaar); the Estekān-shuy, (cup washer); the Qandi, (responsible for serving sugar, rock candy/crystallized sugar (nabāt), and sweets with tea); and the Sar-chāq-kon, or Qalyāndār, (primarily responsible for preparing, lighting, ‘chāq kardan’, and serving the qalyan and chopoq). Each of these individuals held a specific role and duty in the coffeehouse’s workflow.

This relatively complex structure and the close, long-term, and sometimes deeply trust-based relationships between regular customers and coffeehouse staff present a significant contrast to the atmosphere of most contemporary coffee shops and cafés, which typically have simpler service structures and more formal relationships. In the past, knowing or having a friendly relationship with the Qahveh-chi or even a reputable Chāy-forush was considered a form of prestige and a matter of pride for many customers, and could signify their social standing and influence within the neighborhood.

Coffeehouse Transformations in the Modern Era: From Tradition to Modernity

Entering the Qajar period, although the deep-rooted tradition of coffee drinking—especially bitter, Ottoman-style coffee persisted among some courtiers and the aristocracy, the consumption of tea rapidly became widespread among the general Iranian populace with the introduction and significant expansion of samovar use. It is said that the first samovars were introduced to Iran during the chancellorship of Amir Kabir, and this novel device made it possible to prepare tea in large volumes with greater ease. Coffeehouses played a crucial role in this cultural shift, transforming into primary centers for serving richly colored brewed tea from large, gleaming samovars. As noted in the travelogues of some European visitors of that era, Qajar Iran was replete with thriving coffeehouses that, in terms of number and patronage, even surpassed some other traditional gathering places. During this period, tea, particularly among the common people seeking a warmer and more affordable beverage, was considered a healthier and more desirable option compared to some alternatives.

In the 20th century, with increased cultural and commercial interactions between Iran and Western countries, new styles of public venues for leisure, socializing, and beverage consumption, such as modern cafés and restaurants modeled on European examples gradually emerged in major Iranian cities, especially Tehran. These new spaces, with their different architecture, more diverse menus (including new types of coffee, pastries, and sometimes food), and novel social functions, quickly gained popularity among younger, educated urban generations and the middle and upper classes, becoming serious competitors to traditional coffeehouses with their older structures and functions. Furthermore, the gradual availability of tea and later coffee preparation tools in homes reduced the exclusive reliance on coffeehouses for consuming these beverages.

Despite all these transformations and challenges, traditional coffeehouses did not entirely vanish from Iran’s social landscape. Many of them, particularly in the historical districts of cities, old neighborhoods, traditional bazaars, or among specific guilds and merchant communities, continue to operate. These establishments, often preserving a part of their nostalgic and traditional ambiance, remain popular haunts for their loyal, older patrons—and also offer a unique experience for the new generation or tourists—by serving strong, dark tea (chāi-e-debesh), qalyan, and sometimes simple, beloved breakfast items like omelets or dizi (a traditional stew). Some of these old venues are even recognized as part of the cultural tourism attractions of cities.

In contemporary times, alongside the continued activity of traditional coffeehouses, we also witness efforts to revive or redefine their cultural role. Some cultural activists and artists, with a nostalgic approach and aiming to preserve this valuable heritage, attempt to reconstruct the atmosphere of authentic old coffeehouses and revive some of their forgotten functions like Naqqāli, Shahnameh-recitation, or pardeh-khāni (scroll-based recitations), albeit often on a limited or occasional basis. On the other hand, new spaces are also emerging, inspired by the name and some elements of coffeehouse tradition but equipped with more modern facilities, services, and designs (such as café-galleries or café-bookstores). These strive to create a bridge between tradition and the cultural and social needs of today’s society. The main challenge for both approaches is finding a balance between preserving authenticity and appealing to a contemporary audience, especially the younger generation.

The culture of coffeehouses and similar public gathering places for drinking and socializing is not unique to Iran; it has deep and comparable historical roots in many neighboring countries and across the Middle East and Central Asia region, each having undergone its own specific transformations. For example, in Turkey, coffeehouses (often called Kıraathane, and more commonly places for drinking tea and playing board games rather than traditional Turkish coffee) have played an important role in social life since the Ottoman Empire and remain popular venues for conversation, reading newspapers, and social interaction, especially among older men. Similarly, in countries like Afghanistan and Tajikistan, teahouses (Chāikhāna) continue to operate as vital centers for community gathering, rest, and social exchange in both urban and rural areas, forming part of the fabric of daily life, although these spaces too have not been immune to the impacts of modernity and lifestyle changes. These cultural commonalities and differences highlight the historical importance and dynamic nature of this social institution across a vast expanse of the region.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy or a Fading Memory?

As we have explored in detail throughout this article, the coffeehouse (qahveh-khaneh) in Iran has been, and in many ways continues to be, a phenomenon far beyond a simple venue for drinking tea or coffee. From its earliest days of formation in the Safavid era, this dynamic social institution transformed into a stage for the exchange of news and ideas, a hub for preserving and transmitting oral traditions and folk arts such as Shahnameh-recitation, Naqqāli (storytelling), and later, coffeehouse painting. It also served as a haven for entertainment and games, and even, during critical historical junctures, a center for influential social and political gatherings and decision-making. With all its diverse and sometimes contrasting functions, the coffeehouse has been an inseparable part of the urban fabric and the historical and cultural memory of Iranians over many centuries.

With the passage of time and in the face of profound social, cultural, and economic transformations, especially in the last century with the emergence of modern competitors like cafés and restaurants, the role and function of traditional coffeehouses have undergone many changes. Shifts in lifestyle, new patterns of leisure, and the decline of some past oral and performing traditions have diminished their former prominence and centrality in many urban societies. However, as we have seen, traditional coffeehouses have not completely disappeared from the Iranian social scene. Some continue to exist as valuable symbols of the past and cultural attractions, particularly in the historical districts of cities, while others, by adapting to new needs or retaining loyal patrons, still serve as gathering places for certain groups of citizens. Scattered efforts to revive the cultural aspects of this ancient heritage also signify its perceived importance and potential capacity.

Coffeehouse culture, whether as a living, breathing memory found in the nooks and crannies of cities or as an influential chapter of Iran’s social history, is a precious and thought-provoking heritage. Understanding its various dimensions significantly aids in better comprehending Iranian society and culture, both past and present. Studying this multifaceted phenomenon not only opens a window to our past and cultural roots but can also inspire approaches for the future of public spaces, urban hangouts, and the continuation of meaningful social interactions in the modern world.

To learn more about other aspects of the rich food and beverage culture in Iran and other parts of the world, as well as to read related historical and cultural analyses, we invite you to explore further specialized articles and guides in our Food & Drink Tourism on the Foodex blog.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

How is authentic traditional coffeehouse tea (Chāi-e Qahveh-khāneh’i) prepared, and what type of tea is typically used?

Traditional coffeehouse tea in Iran is often made by brewing a large volume of black tea, usually ‘Kalemorchei’ (a type of tightly rolled gunpowder-like tea, literally ‘ant-head’) or ‘Barooti’ (gunpowder tea), in large samovars for a relatively long period. This method results in the tea’s dark color and strong, astringent taste. The high concentration of the initial brew is then diluted with boiling water to the customer’s preference when served in a glass or cup.

In old Iranian coffeehouses, were only the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) and epic stories recited?

No, although Shahnameh-recitation and the Naqqāli (traditional storytelling) of epic tales were very significant and well-known parts of coffeehouse culture, they were not the sole forms of performance. Especially from the Safavid period onwards, with the strengthening of Shia Islam, the narration of religious stories, including the virtues and tribulations of the Shia Imams, as well as poetry recitation in various forms (including odes praising dignitaries, ghazals, and other poetic styles), also constituted a considerable portion of the cultural and entertainment programs in these venues.

In which countries neighboring Iran is or was coffeehouse culture also prevalent?

Coffeehouse culture, or similar public gathering places for drinking and socializing, has historical roots and cultural commonalities in many countries of the Middle East and Central Asia. Among the most notable are Turkey, where coffeehouses (or traditional reading houses called Kıraathane) have played a key role in social life since the Ottoman Empire. Additionally, in countries like Afghanistan and Tajikistan, teahouses (Chāikhāna) continue to be active as important centers for social gathering and interaction, particularly among men, with each region maintaining the tradition with its own specific characteristics and evolutions.

What is the English equivalent of the word ‘Qahveh-khaneh’ (قهوهخانه)?

The word ‘Qahveh-khaneh’ is typically translated into English as Coffeehouse or Coffee House. Given that tea is also a primary beverage served in many traditional Iranian coffeehouses and those in some regional countries, the term Teahouse is also sometimes used to describe these places, especially for a non-Iranian or non-regional audience, to better convey their current function.

What is the Arabic equivalent of the word ‘Qahveh-khaneh’ (قهوهخانه)?

In Arabic, the common and idiomatic term for a place similar to a coffeehouse, where coffee and other beverages are served and which serves as a gathering place, is Maqha (مَقهى), or its plural Maqahi (مقاهي). Descriptively, compounds such as Bayt al-Qahwa (بيت القهوة), meaning ‘house of coffee,’ can also be used, although ‘Maqha’ has much more general usage and is recognized throughout Arabic-speaking countries.